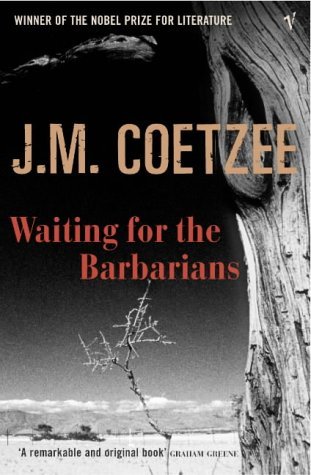

First published:-1980

Star rating:-

It is impossible to read this and not be reminded of an almost genetically programmed inferiority complex, the burden of history only the descendants of the colonized have to bear. Despite those smug pronouncements of the 21st century being an era of a fair and equitable world and the hard battles won in favor of interracial harmony, there's the fact of your friend barely suppressing a squawk of alarm when you express your admiration for Idris Elba - no female I am acquainted with in real life has learned to wean herself away from the fixation with a white complexion. Scrub your skin raw till it bleeds but never fall behind in the race to make it whiter because that's the color the world approves of. You can fawn over Simon Baker's blonde, light-eyed glory but not over Elba's hulking, ruggedly handsome perfection; heaven forbid you prefer the latter over the former. The 21st century is yet to cast its magic spell over the standards of physical beauty.

So if I, a citizen of a purportedly newer and better social order, can still feel the rippling aftershocks of the catastrophe called Imperialism from across the barrier of decades and centuries, what would a man like Coetzee have experienced, stranded in the middle of the suffocating sociopolitical stasis of Apartheid? Moral anguish? A bitter impotence? A premonitory sense of doom? Anger?

Fiction, I believe, must have been his preferred method of exorcizing these demons. And purge these emotions he did through the composition of this slim little novel which can be aptly described as a most heart-wrenching lament on the condition of the world of his times.

It may be true that the world as it stands is no illusion, no evil dream of a night. It may be that we wake up to it ineluctably, that we can neither forget it nor dispense with it. But I find it as hard as ever to believe that the end is near.

An anonymous magistrate stationed at a farthest corner of an unspecified Empire witnesses the death throes of its reign while recovering his own humanity at the loss of his position of power and influence. In the beginning he is convinced of his righteousness as a dutiful servant of the Empire who oversees the welfare his subjects with moderation but with the arrival of a bluntly tyrannical figure of authority whose methods differ vastly from his, he begins to question his own collusion in the maintenance of an unnatural order. Unable to stand as a mute witness to the horrendous abuse inflicted on innocent 'natives' on the false suspicion of their complicity with 'barbarians' or armed rebels who threaten the stability of the Empire, he clashes with the aforementioned administrator who undoubtedly represents the true face of any oppressor when divested of its sheen of sophistication. And thus begins his fall from grace culminating in a kind of metaphorical rebirth through extreme physical abasement.

I was the lie that Empire tells itself when times are easy, he the truth that Empire tells when harsh winds blow. Two sides of imperial rule, no more, no less.

In the fashion of Coetzee's signature didacticism the novel is rife with allegorical implications but as much as these can be deeply thought-provoking, sometimes they also resemble conveniently inserted contrivances. Like the pseudo-erotic entanglement that develops between the ageing magistrate and a young 'barbarian' girl who is left maimed and partially blinded after a violent bout of interrogation is amply demonstrative of a colonizer-colonized arrangement - the one bereft of power to drive the relationship in a desired direction becomes dependent on the volatile benevolence of the other party. Or the mounting paranoia about the anticipated attack of the 'barbarians' who, much like Godot, fail to appear and remain a myth till the end although emerging as the key factor hastening the impending demise of Empire. All the layers of meaning and symbolism could send a dedicated literature student into paroxysms of pleasure no doubt.

With the buck before me suspended in immobility, there seems to be time for all things, time even to turn my gaze inward and see what it is that has robbed the hunt of its savour: the sense that this has become no longer a morning's hunting but an occasion on which either the proud ram bleeds to death on the ice or the old hunter misses his aim; that for the duration of its frozen moment the stars are locked in a configuration in which events are not themselves but stand for other things.

Wary as I am of Coetzee's often stilted world-building, my 5-star rating was an inevitability given my obsession with narratives containing a discernible vein of literary activism in harmony with notions of social justice. Here he also seems to have successfully reined in his pesky habit of turning his characters into sockpuppet-ish mouthpieces to tout his own passage-length worldviews. The narrator does occasionally morph into a pedagogue but his inner monologues never seem out of place given his unique circumstances. Besides it takes courage to acknowledge the fact of white man's guilt in a world which is yet to discard the rhetoric of 'white man's burden'.

No comments:

Post a Comment