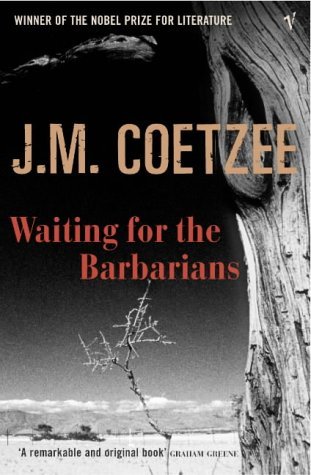

First published:-

1980

Star rating:-

It is impossible to read this and not be reminded of an almost genetically programmed inferiority complex, the burden of history only the descendants of the colonized have to bear. Despite those smug pronouncements of the 21st century being an era of a fair and equitable world and the hard battles won in favor of interracial harmony, there's the fact of your friend barely suppressing a squawk of alarm when you express your admiration for Idris Elba - no female I am acquainted with in real life has learned to wean herself away from the fixation with a white complexion. Scrub your skin raw till it bleeds but never fall behind in the race to make it whiter because that's the color the world approves of. You can fawn over Simon Baker's blonde, light-eyed glory but not over Elba's hulking, ruggedly handsome perfection; heaven forbid you prefer the latter over the former. The 21st century is yet to cast its magic spell over the standards of physical beauty.

It is impossible to read this and not be reminded of an almost genetically programmed inferiority complex, the burden of history only the descendants of the colonized have to bear. Despite those smug pronouncements of the 21st century being an era of a fair and equitable world and the hard battles won in favor of interracial harmony, there's the fact of your friend barely suppressing a squawk of alarm when you express your admiration for Idris Elba - no female I am acquainted with in real life has learned to wean herself away from the fixation with a white complexion. Scrub your skin raw till it bleeds but never fall behind in the race to make it whiter because that's the color the world approves of. You can fawn over Simon Baker's blonde, light-eyed glory but not over Elba's hulking, ruggedly handsome perfection; heaven forbid you prefer the latter over the former. The 21st century is yet to cast its magic spell over the standards of physical beauty.

So if I, a citizen of a purportedly newer and better social order, can still feel the rippling aftershocks of the catastrophe called Imperialism from across the barrier of decades and centuries, what would a man like Coetzee have experienced, stranded in the middle of the suffocating sociopolitical stasis of Apartheid? Moral anguish? A bitter impotence? A premonitory sense of doom? Anger?

Fiction, I believe, must have been his preferred method of exorcizing these demons. And purge these emotions he did through the composition of this slim little novel which can be aptly described as a most heart-wrenching lament on the condition of the world of his times.

It may be true that the world as it stands is no illusion, no evil dream of a night. It may be that we wake up to it ineluctably, that we can neither forget it nor dispense with it. But I find it as hard as ever to believe that the end is near.

An anonymous magistrate stationed at a farthest corner of an unspecified Empire witnesses the death throes of its reign while recovering his own humanity at the loss of his position of power and influence. In the beginning he is convinced of his righteousness as a dutiful servant of the Empire who oversees the welfare his subjects with moderation but with the arrival of a bluntly tyrannical figure of authority whose methods differ vastly from his, he begins to question his own collusion in the maintenance of an unnatural order. Unable to stand as a mute witness to the horrendous abuse inflicted on innocent 'natives' on the false suspicion of their complicity with 'barbarians' or armed rebels who threaten the stability of the Empire, he clashes with the aforementioned administrator who undoubtedly represents the true face of any oppressor when divested of its sheen of sophistication. And thus begins his fall from grace culminating in a kind of metaphorical rebirth through extreme physical abasement.

I was the lie that Empire tells itself when times are easy, he the truth that Empire tells when harsh winds blow. Two sides of imperial rule, no more, no less.

In the fashion of Coetzee's signature didacticism the novel is rife with allegorical implications but as much as these can be deeply thought-provoking, sometimes they also resemble conveniently inserted contrivances. Like the pseudo-erotic entanglement that develops between the ageing magistrate and a young 'barbarian' girl who is left maimed and partially blinded after a violent bout of interrogation is amply demonstrative of a colonizer-colonized arrangement - the one bereft of power to drive the relationship in a desired direction becomes dependent on the volatile benevolence of the other party. Or the mounting paranoia about the anticipated attack of the 'barbarians' who, much like Godot, fail to appear and remain a myth till the end although emerging as the key factor hastening the impending demise of Empire. All the layers of meaning and symbolism could send a dedicated literature student into paroxysms of pleasure no doubt.

With the buck before me suspended in immobility, there seems to be time for all things, time even to turn my gaze inward and see what it is that has robbed the hunt of its savour: the sense that this has become no longer a morning's hunting but an occasion on which either the proud ram bleeds to death on the ice or the old hunter misses his aim; that for the duration of its frozen moment the stars are locked in a configuration in which events are not themselves but stand for other things.

Wary as I am of Coetzee's often stilted world-building, my 5-star rating was an inevitability given my obsession with narratives containing a discernible vein of literary activism in harmony with notions of social justice. Here he also seems to have successfully reined in his pesky habit of turning his characters into sockpuppet-ish mouthpieces to tout his own passage-length worldviews. The narrator does occasionally morph into a pedagogue but his inner monologues never seem out of place given his unique circumstances. Besides it takes courage to acknowledge the fact of white man's guilt in a world which is yet to discard the rhetoric of 'white man's burden'.

First published:-

1999

Republished by:-

Dzanc Books, Open Road Media

Star rating:-

For the past few weeks the subject of responsible use of freedom of expression and speech has dominated our public discourse. And this is not in the context of Charlie Hebdo. A group of Indian stand up comics had collaborated on a live 'roast' of two Bollywood actors (the very first of its kind in India) and posted the video on youtube - a performance peppered with sexual innuendos and a mind-boggling amount of profanity. The video went viral within minutes, inspired twitter hashtags, gave netizens a few good laughs, and 'offended' the usual suspects. A few days later, probably following the diktats issued by self-appointed guardians of Indian culture and values, the video was removed from youtube and criminal cases registered against the participants in this venture for 'obscenity'.

For the past few weeks the subject of responsible use of freedom of expression and speech has dominated our public discourse. And this is not in the context of Charlie Hebdo. A group of Indian stand up comics had collaborated on a live 'roast' of two Bollywood actors (the very first of its kind in India) and posted the video on youtube - a performance peppered with sexual innuendos and a mind-boggling amount of profanity. The video went viral within minutes, inspired twitter hashtags, gave netizens a few good laughs, and 'offended' the usual suspects. A few days later, probably following the diktats issued by self-appointed guardians of Indian culture and values, the video was removed from youtube and criminal cases registered against the participants in this venture for 'obscenity'.

Miscreants who vandalize churches, demolish mosques, rape women or launch into vitriolic diatribes against a specific religious community are allowed to function within the legal framework of the state but citizens who take to the streets to protest against the aforementioned atrocities are either water-cannoned or arrested with astonishing swiftness. Now it seems stand up comics, who are trying to inject some novelty into our painfully predictable entertainment industry which churns out lame potboilers by the dozen month after month, have secured a spot for themselves in the list of 'enemies of the state'. Law enforcement has its priorities right.

Far fetched a parallel as it may seem, Rikki Ducornet's richly imaginative, Bohemian novel harps on the same double standards of moral policing. You can dismiss that glaring'erotica' label (not that I have any problems with this tag), dive in without hesitation and let Ducornet overwhelm your senses with her gossamer fine prose and her evocation of a turbulent Paris during the years of the Revolution. If you are looking for titillation and descriptions of sadomasochistic practices ala Sade, then let me forewarn you, the transgressions alluded to in Sade's monologues are not as frightfully repulsive as one might expect them to be. The only erotic similies I came across are of the following kind -

..although the apple was as wrinkled and bruised as the clitoris of an old whore...

The plot weaves its way in and out of an imaginary Gabrielle, a fan-maker famous for her pornographic etchings and illustrations, and her patron Sade's points of view, stringing together their correspondence through letters during the time both were incarcerated for heresy by the Comité de surveillance while also including a parallel, semi-fictional narrative of the Catholic Church's barbaric suppression of indigenous pagan practices of Mayan people in the Yucatan peninsula during the Spanish Inquisition. Aside from all this there are various fascinating tidbits on Sade's upbringing and stories within stories which are aimed at highlighting the importance of unfettered freedom of thought.

A book is a private thing, citizen; it belongs to the one who writes it and to the one who reads it. Like the mind itself, a book is a private space. Within that space, anything is possible. The greatest evil and the greatest good.

The portions containing Sade's letters have him refuting the allegations levelled against him by the Comité by claiming most of what was regarded blasphemous in his work was simply the product of his virile imagination and that no sex act was ever performed without consent. The Marquis alternately laments the loss of his friend and confidante, Gabrielle and her lesbian lover Olympe de Gouges (an actual feminist figure from the Revolution) both of whom were put to death by the Comité, and chastises the hypocrisy of the Revolution which was systematically destroying the ideals of a civilized society in the name of upholding them.

Once the Revolution has gorged on the citizens of France and returned to her den to sleep for a century or two, what will happen to the triumvirate she whelped: Liberty, Equality, Fraternity-that vast heresy! That near impossibility! That acute necessity!

If you, like me, had not spared a thought for the infamous Parisian libertine till now then do pick up Ducornet's spirited defense of Sadeian ideology of unshackling one's life and art from hypocritical moral constraints. There's a good chance she may arouse your curiosity enough to want to take a peek into Sade's world of amoral creativity. In Gabrielle's own words -

Sade offers a mirror. I dare you to have the courage to gaze into it.

____

Review also published on

Goodreads and Amazon.

**

Thanks to Netgalley and Open Road Media for an advance reader's copy**

First published:-

1924

Star rating:-

Read in:-

December, 2014

Make no mistake. This, to me, will always be Forster's magnum opus even though I am yet to even acquaint myself with the synopses of either Howards End or Maurice. Maybe it is the handicap of my Indian sentimentality that I cannot remedy on whim to fine-tune my capacity for objective assessment. But strip away a colonial India from this layered narrative. Peel away the British Raj too and the concomitant censure that its historical injustices invite. And you will find this to be Forster's unambiguous, lucid vision of humanity languishing in a zone of resentful sociocultural synthesis, his unhesitant condemnation not merely of racism, casteism, religion-ism and what other noxious, vindictive 'ism's we have had throughout the history of our collective existence but of the fatalistic human tendency of rejecting a simple truth in favour of self-justifying contrivances.

Yes there's the much hyped 'crime' analyzed in the broader context of presupposed guilt and innocence . There's the issue of race, class and privilege factoring into the ensuing judicial process. The ripples of the eventual fallout of this mishap disrupt the frail status quo that all parties on either side of the race divide were tacitly maintaining so far and pose crucial existential questions before people of all communities.

Then there are hypocritical Englishmen who cannot choose between preserving the sanctity of the Empire's administrative machinery and upholding their own prejudices. And hypocritical Indians who righteously accuse the Englishmen of institutionalized hatred while stringently maintaining their own brand of intolerance. But greater than the sum of all these thematic veins is the connecting thread of Forster's sure-footed, measured prose which explores not only the inner lives of the central characters but tries to penetrate the heart of a nation-state in the making.

The India depicted here is a foreign country to me - a time and a place yet to be demarcated irreversibly along lines of communal identities that are presently dominating our political rhetoric. It is of little appeal to the newly arrived umpteenth Englishman but, nonetheless, presents itself as an amalgamation of unrealized possibilities. Not once did my brows knit together in frustration on the discovery of any passage or line even casting a whiff of Forster's bias against the people or the land. My senses were stretched taut all the time in an effort to detect any. Sure, Dr. Aziz is a little infantilized and his importance is sometimes reduced to that of a plot device used for manufacturing the central conflict while Adela Quested, Mrs Moore and Mr Fielding appear before a reader as upright individuals who stand for the truth. The other Indian characters seem to be defined by their general pettiness. But these imperfect characterizations can be more than forgiven in the light of what Forster does accomplish.

The song of the future must transcend creed.

There are times when the narrator's voice dissects the drama unfolding against unfamiliar Indian landscapes with a kind of fond exasperation and times when it dissolves into a withering regret for the way the engines of civilization continue to trundle along towards some catastrophic destiny without ever pausing for the purpose of self-assessment. And it is the profound clarity of Forster's worldviews and his sensitivity and forthrightness in deconstructing the enigma of the 'Orient' that elevates his writing even further.

Perhaps life is a mystery, not a muddle; they could not tell. Perhaps the hundred Indias which fuss and squabble so tiresomely are one, and the universe they mirror is one.

It's not the 'handicap of my Indian sentimentality' after all. Forster sought to extract the kernel of truth buried underneath layers of artifice and his craft could successfully flesh out the blank spaces between that which can be expressed with ease. Those are always worthy enough literary achievements in my eyes.