A year in which you have read 126 books (and still counting ) does put a strain on your ability to decide your top 10 favorites from an already long list of favorite books. So what I'll do to make this problem a bit more approachable is make a list of my personal top 15. Just cannot shorten it anymore.

So here are the first 8. I would list the remaining 7 in another post soon. Hopefully.

15)No magic up on the magic mountain but....

If you are not acquainted with Thomas Mann's The Magic Mountain, perhaps his most revered work aside from Buddenbrooks (which was mentioned by the Nobel committee), then either you are living under a rock or your preferred mode of entertainment is more new age and of little depth. Or you are 12. (Just kidding!) This is famously touted as his literature of ideas and that's largely true, but what isn't mentioned in the blurb is what a rigorous slog this is. I spent three excruciatingly slow months navigating the world of Hans Castorp's queer illness, his bizarre invalid set of companions keeping him company in a sanatorium in the Swiss Alps with their quirky and often provocative worldviews. It was a rewarding read, a book which must be read for Mann's elegant language (get the John E. Woods translation not the Lowe-Porter one which is pathetically horrendous) and his statement on Europe's inner conflicts prior to the onset of the First World War. But it didn't leave me with any sense of satisfaction and slightly cheated to be honest.

14)The embers that refuse to die

Don't worry I won't chastise you if you haven't ever heard of this book. Sándor Márai is an obscure Hungarian writer after all who was virtually unknown all his life and hounded by the Communist government who eventually drove him away first to Italy, later to the United States. He was published first in the U.S. where he lived till his death in 1989. Now Embers is a very quiet, introspective kind of book. It delights in recalling the old-world extravagance of the Austro-Hungary empire and merging the past with the present. It has some ornately crafted sentences which are bound to be admired by any reader with an appreciation for great prose. Embers is atmospheric, melancholic, eerie and drips with a regret and longing for that which is no more.

13)Ooh scandalous!

Zoe Heller is known for this one book which was shortlisted for the Booker prize in 2003 and unfortunately enough she is often questioned by fans, readers and reviewers alike about why she creates such perfectly despicable characters (seriously people why do you ask such silly questions?). My point is, do not be so narrow-minded like them. What makes literature so priceless is that we get to be acquainted with alternative points of view, even the blasphemous, contentious and seemingly taboo ones. This is one such book which challenges the reader's idea of social decency and walks the thin line of divide between deviance and normalcy. Her characters are all wonderfully crafted, realistic and their conflicts force us to question established notions of morality. Her prose is beautiful and elegant yet easily readable. I couldn't stop myself from giving this book 5 stars.

(Just in case you are still debating whether or not to read this, the story features a juicy sexual affair between a young attractive female teacher and her underage male student, a boy her son's age. Incentive enough? Also remember the Oscar-nominated Cate Blanchett-Judi Dench starrer based on this novel?)

12)The gift of tragedy

This is one of the most hauntingly beautiful and tragic books I have read this year. And since the tragedies that descend on the life of the protagonist here are more clearly delineated than say in Embers, the entailing heartbreak is greater in intensity. Set against the backdrop of the turbulent years of Japanese occupation of Malay (present day Malaysia), this tale of troubled times connects the lives of people of different nationalities and conflicting allegiances in the most poignant manner and creates a moving picture of a collective human tragedy. In terms of narrative sweep, it can almost be called an epic. For a debut novel this book was nothing short of a towering literary achievement and its Booker longlisting in 2007 is thoroughly deserved. The prose is lush, there are gorgeous descriptions of Malaysian culture and its landscapes with a generous sprinkling of Chinese history and Japanese arts. This is the perfect book on south east Asia. And I certainly look forward to reading more of Eng in the future. (His The Garden of Evening Mists was shortlisted in 2012)

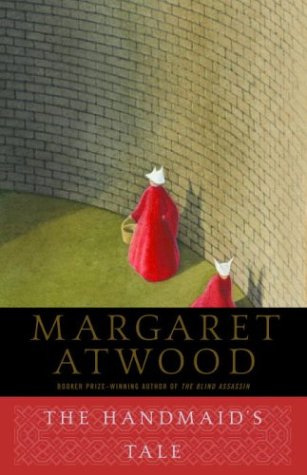

11)Misogynyland

That sub-heading may not sound ingenious or witty but it's the best I could come up with. And frankly, no phrase or sentence will accurately describe this book without the word 'misogyny' in it. Particularly here in India, where we are exactly one year ahead of the barbaric gang-rape of the medical student which sent shockwaves through the fabric of our society and misogyny is deeply ingrained in our psyche and our way of life, this book is relevant now more than ever. Horrifying, coldly brutal and prophetic, The Handmaid's Tale imagines a dystopian society in which women are nothing but baby-producing machines, stripped of their basic human rights and personal liberties, only utilized like inanimate incubators to ensure mankind's survival in terms of numbers. This book will make your hair stand on end. Literature students worldwide are acquainted with this book as a very standard feminist novel and I believe the entire canon of feminist literature will be incomplete without the inclusion of The Handmaid's Tale. And dear men of the world, READ THIS if you haven't already. Please? (This was also shortlisted for the Man Booker in 1986)

10)An ode to the third sex

Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West need no introduction and their memorable affair led to the creation of this slightly under-appreciated masterpiece. Woolf's Mrs Dalloway, The Waves and To the Lighthouse are more universally worshipped while Orlando is often overlooked whenever Woolf's oeuvre is under discussion. Magical, otherworldly, beautiful and fraught with symbolism, Orlando talks about the woman, the man and their mystical united exploration of all dimensions - spiritual and physical. Virginia Woolf is not everyone's favorite but for someone like myself, who will perhaps adore even a meaningless mark she had made with a pen, Orlando was pure bliss. Exquisite prose, phantasmagorical imagery and an unforgettable protagonist. This was Woolf's tribute to Sackville-West and their affair and lifelong friendship. And boy what an incredible homage this is!

9)Collages

A collage of the human consciousness is what this is. Hauntingly beautiful images stitched together with the patience and devotion of a true mistress of the craft. Eerie, surreal and utterly breath-taking. For all those who know Anaïs Nin as a writer of only literary erotica, do not believe that piece of false information. She has written literature, proper literature with the capability of triggering flights of fancy and infusing your reality with the color of your most bizarre dreams. See talking about this book is very difficult without going into hyperbole. So hey, read my review here.

8)The price of motherhood

This is one of those unheard of books that you discover on your random visit to a well-stocked library or a used book store or after a whimsical clicking of the 'request' button on the Netgalley page for Open Road Integrated Media (in my case). And this is one of those surprisingly moving and relevant books that make a powerful statement on a subject less talked about, less discussed. Written in the first person narrative voice, Letter to a child never born, tackles issues like the seriousness of giving birth, a to-be mother's misgivings and the controversial matter of abortion rights. Oriana Fallaci, a powerful Italian war correspondent wrote this book in the 70s when it supposedly became quite a publishing phenomenon. But I believe it has become buried in recent years (only less than 200 reviews on Goodreads) which is why the Open Road Media guys decided to republish it in a new avatar. (Thank god for that!) Even though this book deals with a host of predominantly feminist issues, Ms Fallaci has also done well to give the humanist's point of view here.

Phew that concludes the first part.